“This article is reprinted with permission from CleanerTimes/IWA, a monthly trade journal serving the pressure cleaning and waterjetting industries. For more information please visit www.cleanertimes.com or www.waterjettingdirectory.com . Article by Kathy Danforth

June 2011, p. 42, Cleaner Times

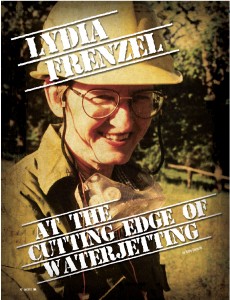

Dr. Lydia Frenzel has been a significant force in the waterjetting industry since her early work in the 1970s and 1980s, which established waterjetting as a superior method for coatings removal. Lydia received her undergraduate and doctoral degrees in chemistry at the University of Texas in Austin and subsequently moved to southern Louisiana, where she worked with anti-fouling hull-coatings and then in pipeyards dealing largely with the effects of corrosion. After growing up on the Gulf Coast of Texas “with the chipping of rust in my ears,” this was a familiar battle.

While 3000–7000 psi water-blasting was used for cleaning pipes, Lydia reports, “When the pump companies started getting up to 20,000 psi around 1981–82, we started getting excited about coatings removal and surface preparation.” The lower pressure would clean and wash salts off, but Lydia observes, “When you go from 10,000 psi to 20,000 psi, magic occurs. You get a sonic wave on the surface and polymers would shear right off. The threshold pressure for most materials was 20,000 psi. I did a white paper for Butterworth on 20,000 psi surface preparation of metals for painting, and the result was that it could be done very elegantly.” Where technical papers typically have an audience of 50–100, around 3000 copies of Lydia’s “Water is True Grit” found their way to tradespersons and it is a classic Web item.

Charles Frenzel, a physicist from Vanderbilt as well as Lydia’s husband and coworker on the Advisory Council, notes, “I don’t know that anyone recognized at that time that we were opening an industry. No real science had been done on the idea of using waterjetting for coatings removal till that point. But when we cleaned the steel, we observed it had an immediate light yellowing that stayed that way for months. We have steel tests in storage that haven’t rusted in years.”

Lydia recalls, “We had a friend at the University of Kentucky who did the metallurgy on a cross section to prove that we had very clean surfaces. We had a small testing lab in New Orleans paint the surfaces for immersion testing, and we found the stuff was really cleaned off. With the waterjetting you not only got the salts knocked off, but the paint adhered better.”

“Immersion testing showed amazing performance!” Charles says, and this provided an application for equipment manufacturers to aim toward. Charles states, “Something had to come along to provide a reason for wanting more pressure, to control it in a certain way, and make a nozzle a certain way. Coatings removal gave people a handle on how this could be done and how it should go forward.”

After a typical cleaning by brushing or abrasive blasting, corrosion would often start within hours. Charles points out, “With abrasive blasting or brushing, they actually weren’t cleaning the salts off. People were looking at it in macroscopic terms—we can’t see anything so it must be ok. But corrosion starts at a microscopic level. By the next day the steel was black again.”

Though pump life was initially a problem with the higher pressures, Lydia notes, “The pump manufacturers have been very good at meeting needs for pumps, nozzles, and pump parts for this industry. They’ve responded to every request the industry has had.”

As waterjetting use expanded, Lydia continued work in related areas. “I worked for a coal mining plant in California and for Baker Sand Control in Lafayette, LA,” Lydia recalls. “My husband, Charles, and I had a computer consulting firm in New Orleans, and we were selling a water-based compound to keep pipes from corroding.”

Lydia became a committee chairperson for the Steel Structures Painting Council, now the Society of Protective Coatings (SSPC), and also for the National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE). “I’m still doing that and that’s still fun,” she comments. “Along the way I became the expert for the United States in this particular area—surface preparation by wet blasting—for the International Standards Organization (ISO).

“The waterjetting community was excited about this application, and those contractors who used it liked it, but they were few and far between,” Lydia observes. “One obstacle comes from contractors who own dry blasting equipment and would have to buy new equipment and re-educate their workforce. Another obstacle is that when you remove the rust, everything on the steel underneath now shows up— where the metal may have been scratched or welded.” With dry blasting, old mistakes are erased since the surface of the metal itself is abraded rather than just exposed. Lydia comments, “It’s still not uncommon to get a certified inspector who doesn’t know what he’s looking at. The surface looks different. But the refineries love the waterblasting because they have to test the little cracks and you can find them easily.”

Charles points out that some corporate cultures do not favor overall efficiency. “They didn’t worry about whether it was cheaper to replace— due to damaging rust from poor surface maintenance—or to repair. It’s cheaper to maintain, but the people who are in operations don’t get promoted by saving money. They are enamored by the shiny and the new.”

However, the advantages of waterjetting were recognized by paint manufacturers and the U.S. Navy. The Naval aircraft carrier repair engineers couldn’t believe the results. Lydia reports, “International Paint, Hempel, Sherwin Williams, PPG, and Ameron said they accepted and actually preferred the waterblasting cleaning method. The coatings suppliers are key because they have to warranty the work. If they don’t like it, nothing’s going to happen.”

“We got a breakthrough in 1994 because the U.S. Navy didn’t want sand left over after they blasted ship hulls. They wanted something ecologically friendly and recyclable, and that’s water,” Lydia states. “They had a demonstration of a full vacuum recovery and full recycling system.” Charles adds, “The waste stream should have no other waste than the coating that comes off. Waterjetting accomplishes this. The paint can be separated out, compressed, dried, and that’s the minimum possible.

Instead of thousands of tons of contaminated abrasive, such as sand, you have 15 barrels of paint chips. Waterjetting is incredibly green.”

Charles and Lydia formed the Advisory Council in 1996 with the goal of promoting education, cooperation, and development of new technologies that conserve resources, primarily dealing with water blasting or wet abrasive blasting. Lydia says, “Charles and I took photographs for NACE/SSPC standards, which were funded by the National Shipbuilding Research Program (NSRP), a joint shipyard/navy program. NSRP is still funding projects favorable to waterjetting.”

Education efforts involve workshops all over the globe, massive e-mail, and multiple websites to introduce users to the waterjetting process, and an ongoing battle against the inertia of doing things the same way they’ve always been done. “After 20 years some people are still wondering if water will dissolve salts,” Lydia wryly comments. “The standards have been out since 1994, and I still have people saying, ‘I’m not sure we can paint over waterjetted surfaces.’”

As Charles points out, “It would be easier to change chemistry than some people’s opinions, and we educators don’t like that!”

Successful waterjetting also calls for a higher level of expertise, which takes time to develop. Lydia explains, “You can calculate what happens when the water hits and ‘splats.’ You can calculate the velocity, energy, and force from a nozzle, and the cohesive force to drill through a layer and the adhesive force to shear along an interface. You can take off exactly the layers you need at a very specific level.

“A lot of the time contractors are not into calculations,” Lydia observes. “They want to pick up the equipment and just have it work, but this is sophisticated. Most of the time blasters will start at an inconspicuous spot with low velocity and pressure, or they might start at 30,000 psi and see what it takes to remove one layer and not the next. It becomes an art.”

Since Europe has been ahead of the United States in their environmental awareness, they have also been ahead in the use of waterjetting technology. Lydia notes, “In the l980s a company in Canada put together a massive waterjetting system and came to the U.S. Now they maintain pipelines in Russia and the Middle East. They come along the pipeline and clean and recoat it, but people in the U.S. aren’t using it even though it’s proven technology.” Charles and Lydia both see restoration of the oil, gas, and chemical pipelines in the U.S. as a critical need where waterjetting could be instrumental. Lydia reports, “Our pipeline system is old and corroded. It’s a major crisis point in our infrastructure. It costs $7 billion annually to monitor, replace, and maintain the 484,000 miles of U.S. pipelines. In our country we’re patching rather than cleaning and repainting.”

Since pipeline ruptures range from disruptive to dangerous, Charles muses, “Why isn’t the refurbishment of the pipeline system of the U.S. recognized as one of the largest business opportunities of recent times?” Charles feels that a vision of what can be achieved is necessary for change to occur. “We’ve got a society that’s so litigation-conscious that they do the same, usual thing,” he remarks. “There’s no incentive to look at something new or different.”

Lydia’s concern is, “After 30 years I don’t see how waterjetting is new any more, but I keep finding people who’ve never thought about waterjetting for their cleaning and coatings removal.”

Lydia served on the WJTA Board for 12 years and says, “I really enjoy working with the waterjetting industry. They’re very competitive, but they will get together and talk about what’s good for the industry. Through the years they’ve been very cooperative.”

Because of its versatility, waterjetting has quite diverse applications. “I love it that you can go into someone’s research lab and they may be cutting stained glass or parts for a motorcycle fender,” Lydia exclaims. “It’s used as a cutting tool for blue jeans, mashing potatoes, and pulverizing orange juice. One of the biggest uses of waterjets is cutting baby diapers because you have a fast stream of water that doesn’t get anything wet. It’s a knife blade that never gets dull. I would love to see more water used on bridges, structures, and roads. It pains me to see someone with a jackhammer on a highway. With waterjetting you can remove what you want without fracturing the rest of the surrounding concrete.”

Lydia has enjoyed serving as an expert on unique projects where waterjetting could provide both the precision and power needed. “We were involved in the conservation of the Titanic Big Piece and the Saturn V rocket,” she recalls. “I found the Saturn V to be the most interesting because you’re working on an icon—a part of history. We worked with the conservators to use waterjetting and not damage the artifact. We were letting them know how you could get one coat off without tearing the rest to pieces.”

The reason for Lydia and Charles’s promotion of waterjetting is not just professional interest; Charles says, “You might think we’re just technologists, but we think about the welfare of people. We search for excellence.” Since Lydia has been a District Governor with Rotary International, they have visited hundreds of clubs and Charles observes, “Community-aware people do not come from the engineering and science professions, but they have the biggest impact on lives. Scientists are often not aware of social implications because living in a gated community doesn’t give a picture of what’s going on at the food bank.”

“We really hate to see the ill effects of misapplied techniques and old ideas because people don’t want to change,” he continues. “That’s why we got involved—we were concerned about the waste of money and lives. We needed to develop a network to bring this community together to look at conservation of resources and the infrastructure of the United States.”

Lydia has been recognized as “Distinguished Citizen” by Alpha Gamma Delta sorority and was honored in 2004 as one of the 20 most influential people in the coatings industry by the Journal of Protective Coatings and Linings. As well as giving workshops and providing expert advice, Lydia and Charles have found time to write seven fiction books, with the latest released January 2011. Charles accurately says, “We do a lot of things!” From the ground up, Lydia has been pushing the water-jetting frontier forward, and she welcomes others to join her to build the future with action and vision!

Drs. Charles and Lydia Frenzel live in San Marcos, TX, and can be reached at Frenzelfrenzel@advisorycouncil.org.

IWA Jun 2011 45

August 3, 2011 at 4:13 am

A good summary of Lydia’s technical achievements for people who have not been lucky enough to meet her